Long before Sept. 18, 2003, when a street in Ankara was named after Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian poet, philosopher and humanist, late Ottoman intellectuals were deeply inspired by Tagore and his vocal internationalism and humanism.

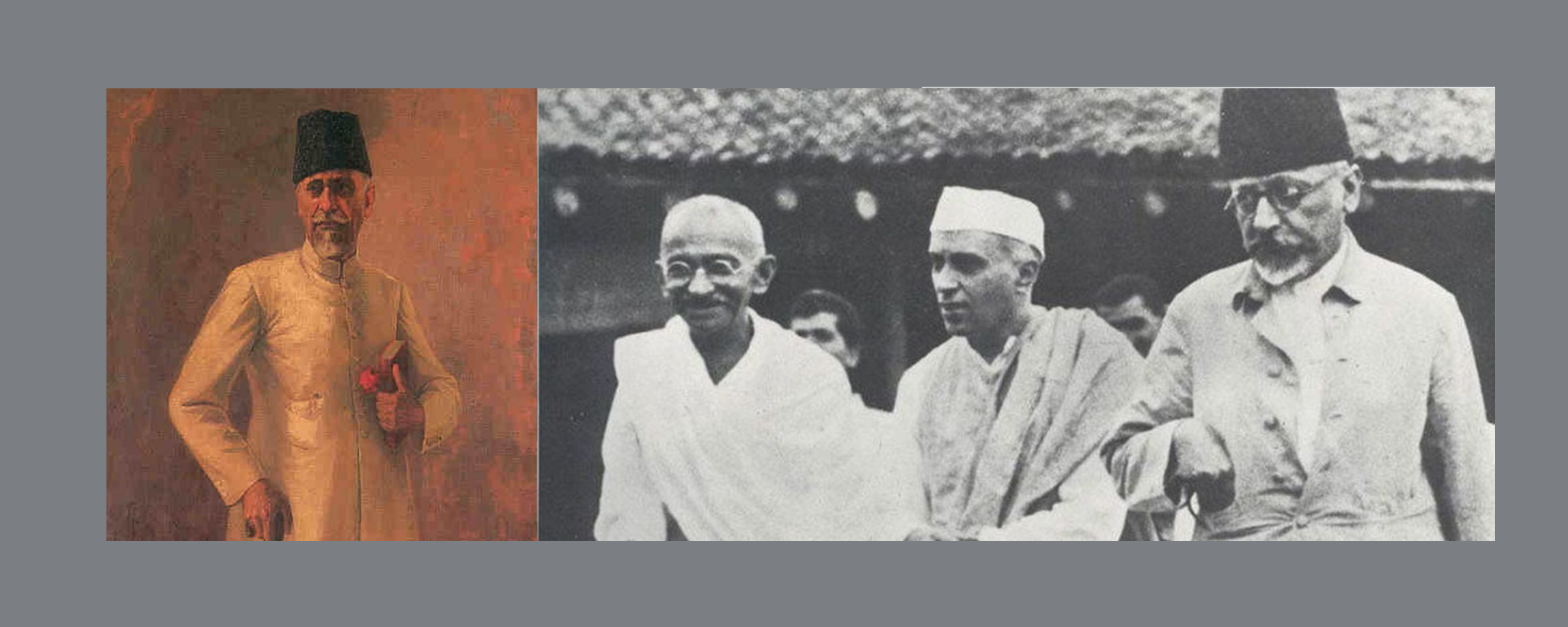

An Indian who was equally critical of Asian society’s weakness as well as the exploitative Western colonialism, Tagore saw in the Turkish republic’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a new hope for Asia and its resurgence. In his tribute to Atatürk, he had said, “Kemal set us an example of a resurgent Asia … he carried out a crusade against the tyranny of superstition.”

When a new Turkey was successfully emerging as a modern nation-state, Fethi Tevetoğlu, the first Turkish biographer of Tagore in 1938, said, “I wonder whether my sympathy (for Tagore) is caused by my interest for India and for the Indian soul. Or is it because Tagore is an Oriental?”

Tagore inspired a Turkish generation that was going through the very rough time of the Ottoman decline and the Western occupation of its territories in the aftermath of World War I. The generation of despair looked to Asia’s anti-colonial struggles and Japan’s industrial rise as inspiration for new hope of intellectual resistance to the West.

This had led to the rise of a new genre of politicians in Turkey, known as pan-Asianists, who were looking to Japan for their material growth and to India for their spiritual and intellectual pursuits.

This was the time when Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi started attracting global attention with his unique politics of nonviolent resistance. Gandhi and Tagore were the two top icons of the new Indian philosophy.

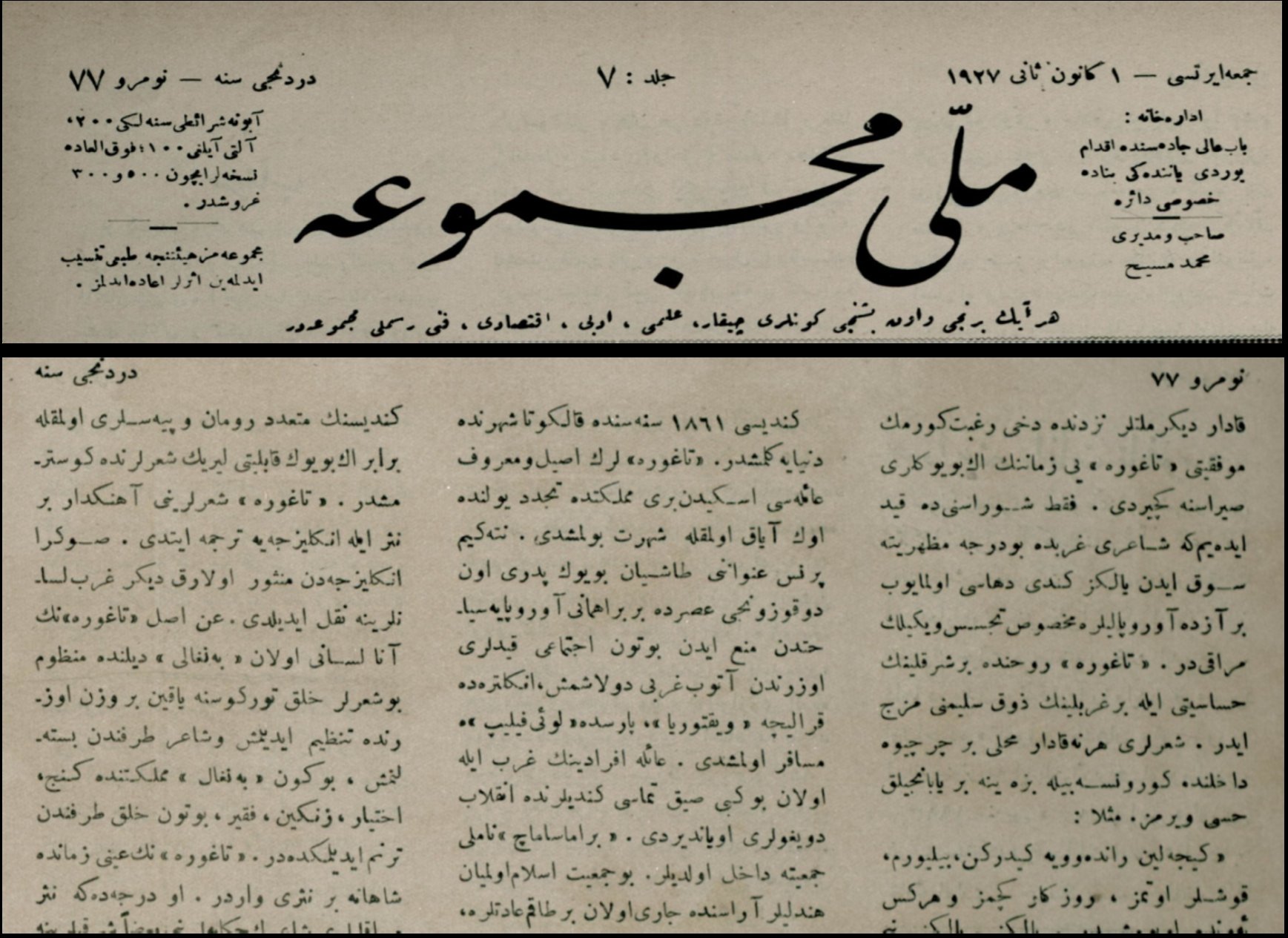

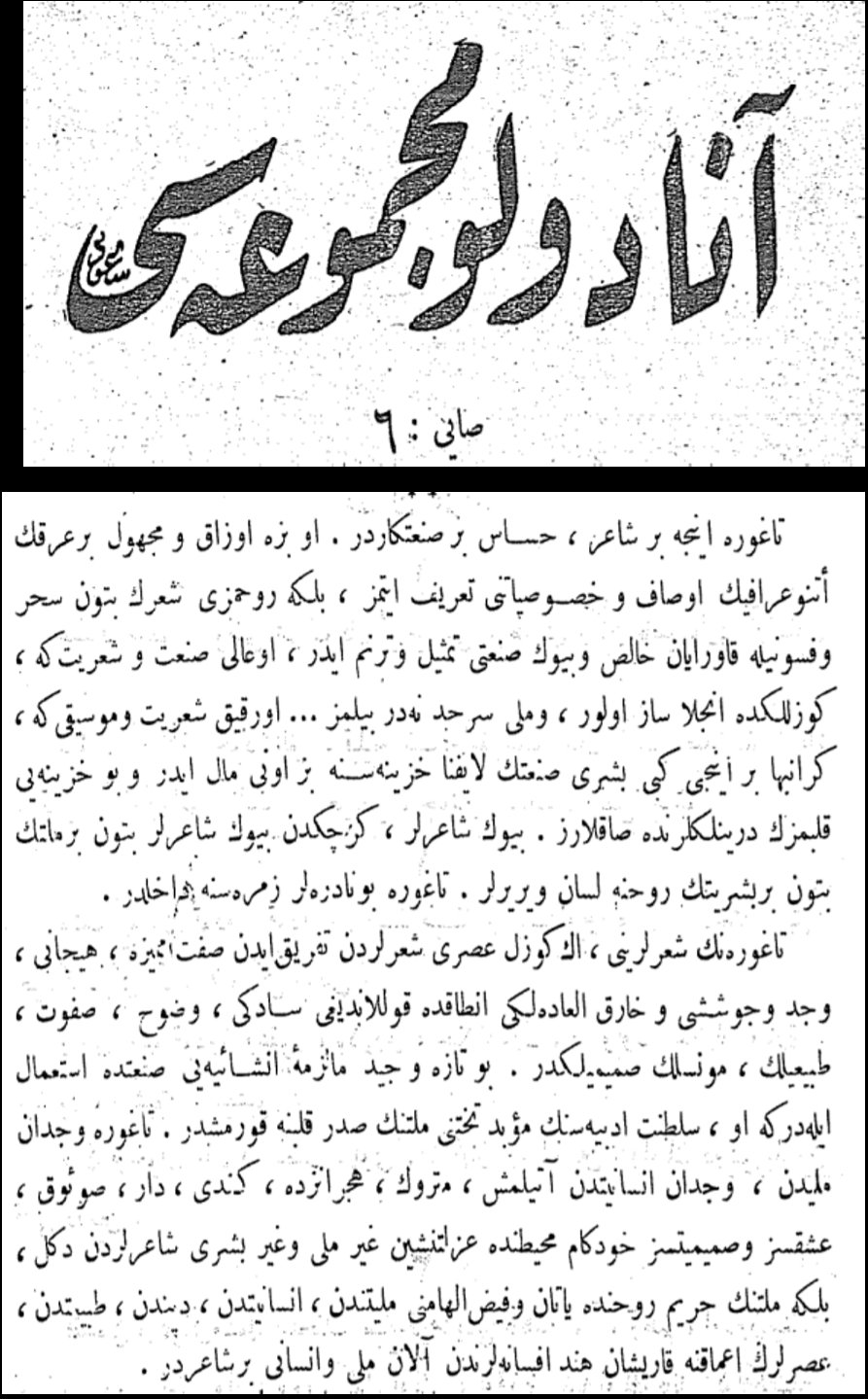

In the declining days of the Ottoman Empire, the Ottoman Turkish language newspapers and journals of the 1920s were covering Tagore’s international travel, his speeches and publications with great interest. Ottoman journals and early republican journals such as Sebilü’r-Reşad, Anadolu Mecmuası, Idjtihad, Hayat and Milli Mecmua were regularly following Tagore’s works and had started translating some of his works into Ottoman Turkish.

“The Home and the World” (1928), was the first novel of Tagore translated by Bedri Tahir in Ottoman Turkish. In later years, almost all of his works were translated into the Turkish language. “The Gardener,” “Fruit Gathering,” “The Crescent Moon,” “Gitanjali,” “The Post-Office,” “The Fugitive,” “Stray Birds,” “The Home and the World,” “Chitra,” “Lover’s Gift,” “The Religion of the Poet,” “Gitanjali” and “The Cycle of Spring” have been translated and widely publicized for Turkish readers since then.

Tagore’s works had a special appeal for the late neo-Ottoman pursuits of establishing a modern, liberal and multicultural nation where all citizens could enjoy equal rights. In his definition of a nation, Tagore was opposed to European nationalism, which was conceived around narrow ethnic, linguistic and even religious biases.

This had led to racial, linguistic and ethnic conflicts within nations. Many Ottoman Turks wanted to transform Turkey into a multilingual, multiethnic and united Ottoman Vatan and were inspired by the rise of Asians and especially the Meiji Japan of the 1800s.

In Tagore, many Ottomans and even early republicans saw an intellectual patron of their modern and progressive aspirations. In one of the small articles on Tagore, a journal, Dergah writes on Aug. 5, 1920, “The biggest guard of India’s independence sings the song of freedom to Indian children in the peace march in the forests of the Gulf of Bengal; he, walking barefoot, sang the songs of freedom and songs of free birds.”

In the Jan. 1, 1927 issue of Milli Mecmuasi, Dr. Safia Sami said: “Tagore successfully mixes successfully sensitivity of the East and aesthetic perfection of the West. Howsoever his poetry appears of a local context, it doesn’t give the feeling of foreignness.” She finds Tagore’s appeal as global as Tolstoy’s and Dostoevsky’s, thanks to his compelling narration of subjects of universal values of love, longing and nature.

With his message of fraternity and peace, Safia says, Tagore became a Murshid (spiritual guide) among all nations, a role for which he established the Shanti Niketan, the fort of peace (Sulh Kilasi). In 1924, Hasan Cemil published an emotional introduction of Tagore in “Anadolu Mecmuasi” in which he wrote: “With his delicate poetry and music, Tagore stands out unique among all his contemporaries. With his best elements of excitement, ecstasy, marvel, simplicity, clarity, and naturality, Tagore became eternal in the Kingdom of Literature (Saltanat-e-Edebiyatisin).”

Cemil writes, in his Oxford lecture, Tagore appeared as “a guide of India’s message to the world, a spiritual guide, like a prophet of a religion.” In 1920, Sebilü’r-Reşad, a journal edited by Turkey’s national poet Mehmet Akif, published a series of translated articles to introduce Tagore and his literary works in four parts.

The series titled “Japonya’da Milliyet-II: Nobel Mükafatını Kazanmakla Bütün Cihanda Temayüz Eden Hindistanlı Şair-i Muazzam Tagore’nin Konferansı” (The lectures of world-famous Noble laureate Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore) is mainly a detailed report of Tagore’s visit to Japan in 1920 and his lectures and meetings in Japan. This was the time when many Ottoman officials were still looking to make an alliance with the Pan-Asianist Japanese.

In this sense, Tagore’s ideas were providing an intellectual ground for unity and solidarity among Asians so that they could come out from the yoke of colonialism. Interestingly, at this time, some

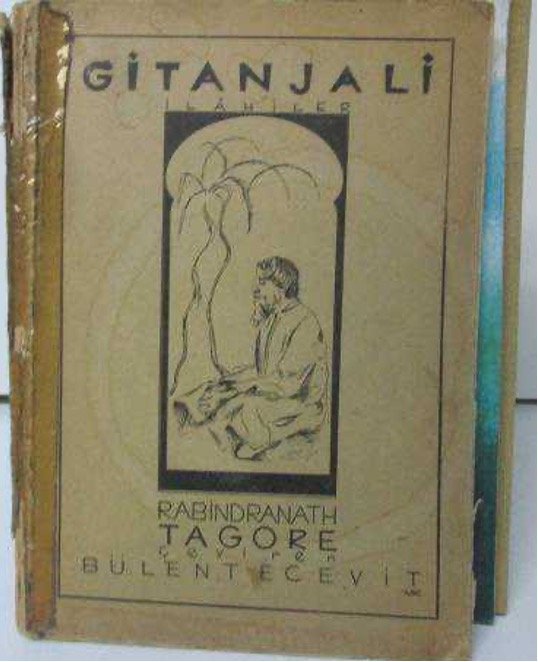

A 1941 edition of Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit’s translation of “Gitanjali.”

Ottoman Turks were already based in Japan and were actively interacting with Indian freedom fighters, among them, was Abdürreşid Ibrahim who, some sources claim, had also met the legendary Indian freedom fighter Subhash Chandra Bose in his Japan sojourn. The Ottoman bureaucrat and literary figure Süleyman Nazif wrote an introduction of Tagore in the Inci journal in which he even called Tagore equal to Omar Khayyam.

In the early republic years, Tagore received the popular attention of the Turkish intellectuals who went on a drive to translate his works into the Turkish language. For example, Ibrahim Aladdin published an article “Hind Şair Tagor’un Mektebi” in Muallimler Birliği magazine in its 22nd volume in 1927.

Büyük Ozan published an article on Turkish translations of Tagore’s works in Turkish in Yarım Ay magazine in its 17th volume in 1936. Elif Ayn wrote the article “Indian Poet Tagore” (“Hint Şairi Tagor ve Mektebi”) for the magazine Yeni Kitap, in the fifth volume of 1927. Mim Said published an article in 1928 “Hint Şairi Tagore’dan” (“From the Indian Poet Tagore”) in Fikirler journal’s 12th volume.

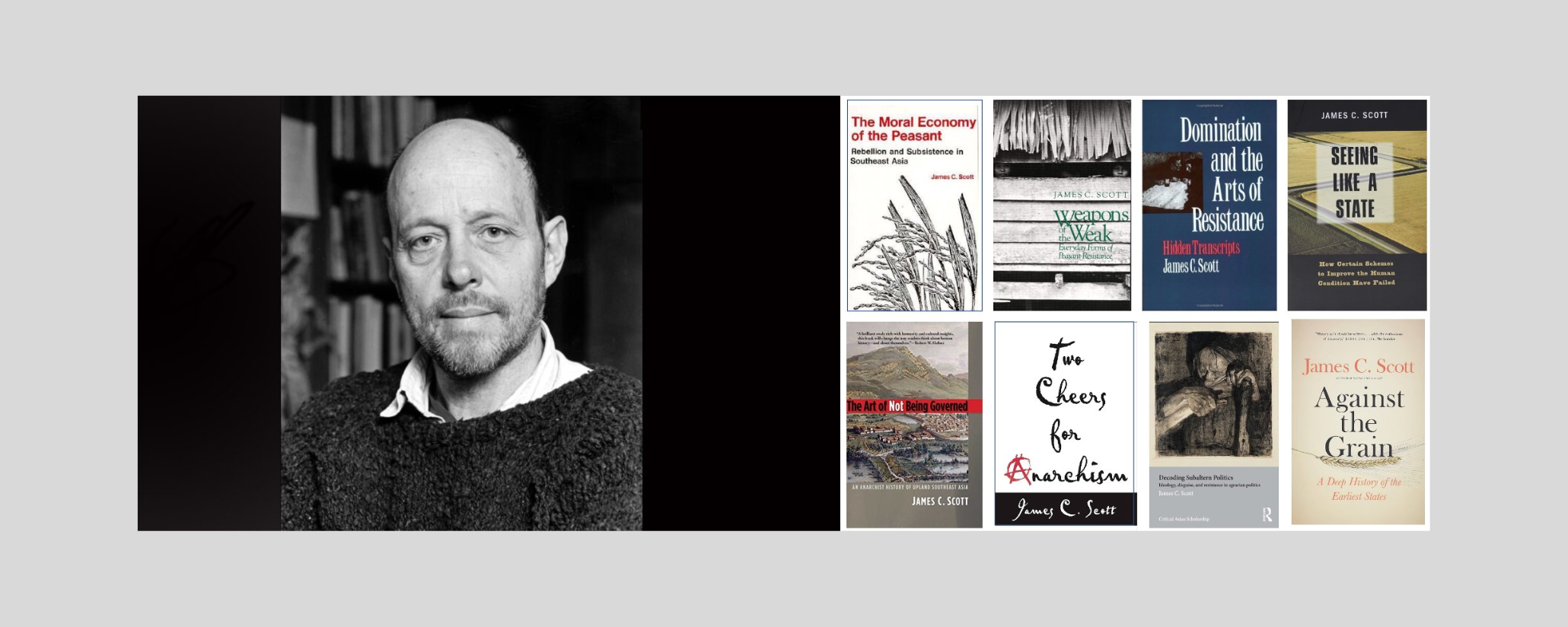

This fascination of Turks, both late Ottoman and early republic era intellectuals, with Tagore remained unchanged for a very long time and influenced the future literary and intellectual traditions in Turkey. So much was Tagore’s spiritual influence that Tagore’s poetic collection “Gitanjali” was translated in Turkish many times, once by none other than Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit himself in 1941.

As the world commemorates Tagore’s 80th death anniversary, Indian and Turkish intellectuals share the memory of Rabindranath Tagore, who had not only traveled to Turkey in 1922 to meet Atatürk but also as a symbol of Asian resurgence. The books gifted by Atatürk to Tagore and exhibited in his institute Shanti Niketan in Kolkata are a reminder that both countries need to cherish these memories to strengthen their friendship.

Dr. Omair Anas is the Director of Centre for Studies of Plural Societies.