After 75 years of India’s Independence, the late commencement of research strengthens the fact that women’s stories and lived experiences have been selectively silenced, unheard of and not encouraged to come out during the extremely violent and prolonged refugee migration during the partition of India. Ironically, women and children have been used chiefly to represent partition trauma.

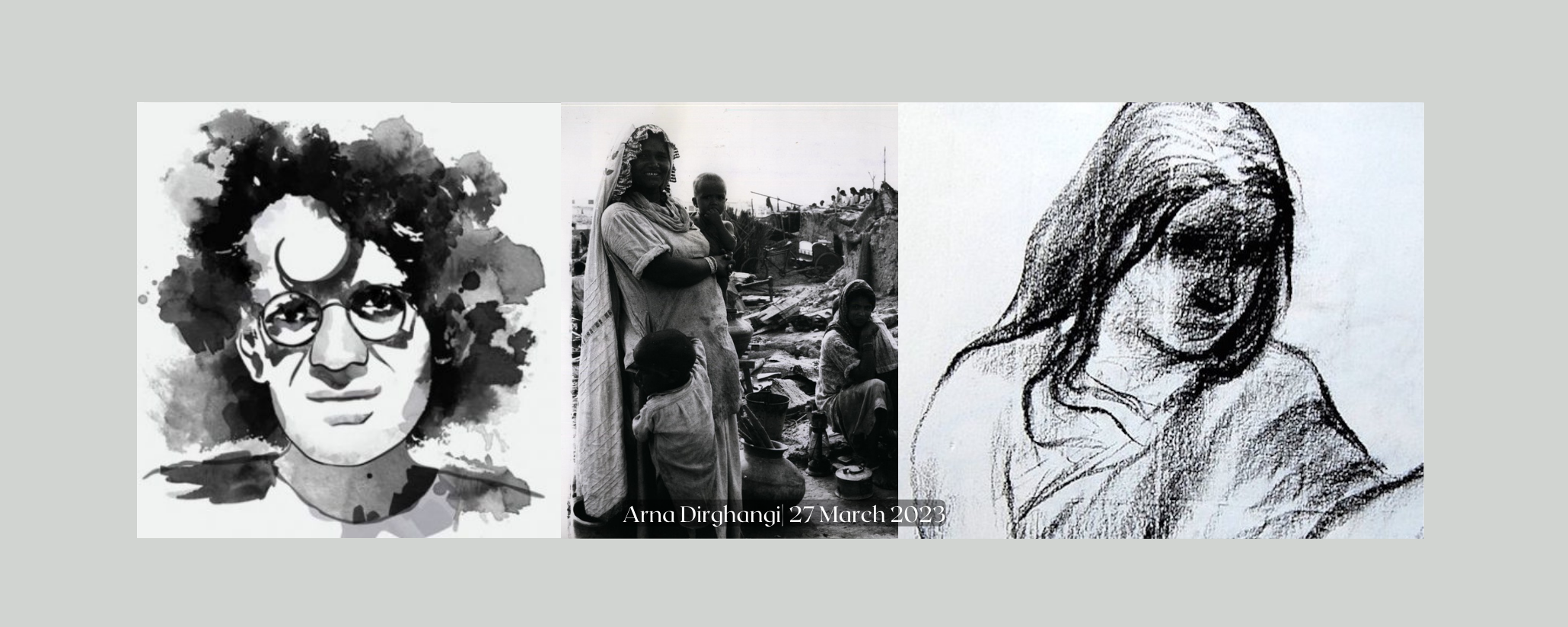

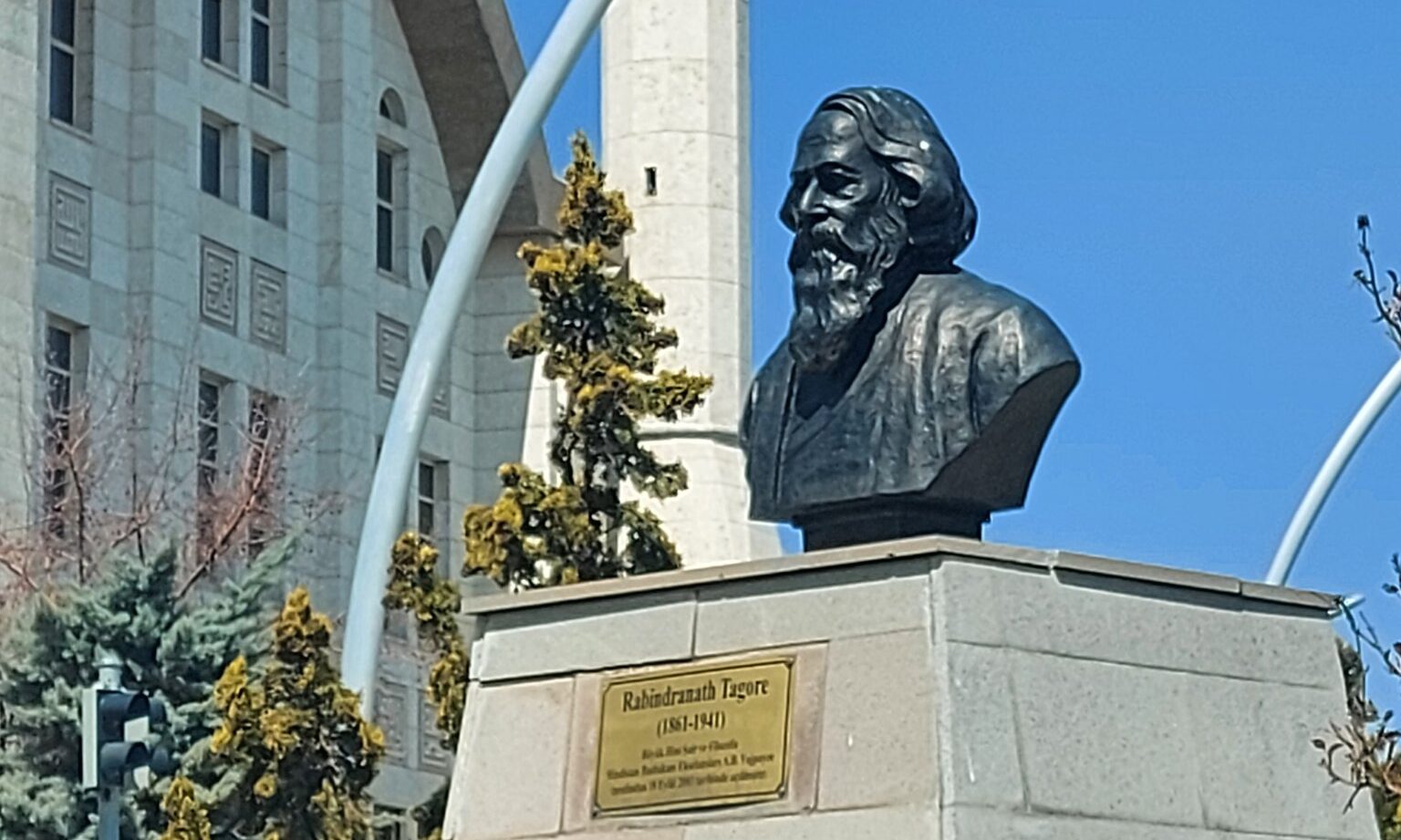

Many contemporary visual representations of the partition of India include the archetypal black-and-white photograph of refugee women or children, with cloth and food bundles untidily strewn beside them, gazing directly into the camera lens. Such a photograph commonly reminds one of the traumas of displacement in a post-partitioned nation. It is a silent fragment of the event captured through the lens. Refugees, towering over twelve or thirteen million, crossed the porous borders of a newly partitioned Indian nation in 1947, many of them women and children. Unarguably the largest forced migration in recorded history, the partition has left an indelible mark on the lives of millions. Seven decades after the event, the trauma continues to trickle down to the next generation of survivors who remember their lost homeland with melancholy.

Separation through borders, united by gendered violence?

Anita Inder Singh mentions that the Indian partition is not the first in global history: it was one of the four on the list of the Raj with Ireland, Palestine and Cyprus. All the nations witnessed dissection on religious lines, per the British divide-and-rule policy. Those in support viewed partition as a “way of containing conflict.” Many “advocates of partition” reinforce the same in hopes of assembling ethnically pure nation-states and containing future atrocities (Singh 2006, 2). This assumption works only in theoretical narratives. The partition proved this hypothesis hugely inaccurate. The partition still exists several years after its physical commencement, with its most devastating consequences occurring later during the large-scale refugee migration. Singh further mentions that partitions have gained legitimacy via the theory of aligning a nation-state with ethnicity, religion, or linguistic unities (Singh 2006, 4). This ideology opposes a “pluralist concept” of a nation-state where multiculturalism abounds. The latter is the concept prevalent in contemporary times. The post-partition political environment remained heavily communally charged throughout the migration. Whatever the religious differences be, the one common experience stitching the trauma of partition on both sides of the border remains the mass abuse, violence, and harassment of the nation’s women.

The “human” dimensions of distress, trauma, and painful memory surrounding partition have often been under covers behind the historical or politically motivated ones. Within that, the erasure of women’s lived experiences during the partition is only beginning to be registered.

Selective silence of females throughout the partition

The “human” dimensions of distress, trauma, and painful memory surrounding partition have often been under covers behind the historical or politically motivated ones. Within that, the erasure of women’s lived experiences during the partition is only beginning to be registered. Urvashi Butalia in her book The Other Side of Silence, talks about discussions as early as September 1947 by the Governments of India and Pakistan to return abducted women to their homes. Failed attempts at reaching a conclusive stance on such rescue postponed the operation. The governments released an Inter-Dominion Treaty around December of the same year. The treaty stated that “…women living with men of the other religion had to be brought back, if necessary, by force, to their ‘own’ homes –in other words, the place of their religion” (Butalia 2000, 111). At this juncture, the curious paradox of the refugee woman stands. The statement that pushed abducted women back to their ‘homes’ from the clutches of another ‘religion’ is a scathing assumption accepting women as Indian citizens based on their religious affinities alone. India’s stance stood on its declaration to be a secular nation, which violated such a treaty. An abducted woman had no voice in determining her home. Further, the refusal to discuss women’s situations through the massive exodus relegated the voiceless to remain that way.

Many such narratives of loss have been primarily oral and, consequently, undocumented. However, academic work on women’s silence has received attention through recording such oral interviews and related narratives on the north-western border. Therefore, in contemporary times, the concept of silence has been a recurring trope in partition literature and research.

The silenced female in Manto’s short stories

Perhaps no writer has adequately caught this silence through his short stories than Urdu author Saadat Hasan Manto. His brutal stories mirror the awful reality of the violence against women, their forced silence in the face of collective violence and selective amnesia during partition. The article discusses the trope of “silence” in one of his short stories, Khol Do (1948). Inside a heavily crowded refugee camp, a desperate father, Sirajuddin, begs the helpers to find his lost daughter Sakina. Several weeks pass, but it seems as if the rescuers cannot find her. Their reassurance, “oh, we will, we will” (Manto 1948, 76), keeps Sirajuddin hopeful. After a few days, he sees an inert female body in the hospital. The girl was luckily rescued in an unconscious state near the rail tracks. To his delight, it is his daughter Sakina. She responds by opening her pants to the words, “Khol do!” (Open it!). These words, however, are the doctor’s instructions to open the window. Sirajuddin is elated that his daughter lives, and the doctor breaks “into a cold sweat” (Manto 1948, 76).

This article further analyses the layers of silence that enshroud the protagonist Sakina and the hidden violence she is a silent victim of. Manto’s sleight of hand lies in what is left unsaid or instead “silenced” in the story. The violence on Sakina is never explicitly mentioned but is to be assumed by the alert reader. Sakina’s response is a wretched signifier of numerous violations before they left her to die near the railway tracks. Many layers of silence cover the short story. Prominent ones include the silent presence of Sakina’s dead mother, the intentional silence of the rescuers (that involves sinister motives), the unintentional (or perhaps unclear?) silence of Sakina’s father, and the all-pervading silence of the doctor.

From the commencement of the story, Sakina’s mother’s brutal death hangs around the ominous landscape of the story. Sirajuddin is reminded of “his wife’s mutilated body, her guts spilling out” (Manto 1948, 74) while he tries to figure out where he lost Sakina in the chaos. Consequently, describing his daughter to the helpers, he claims, “she takes after her mother” (Manto 1948, 75). Sirajuddin’s wife’s gruesome death lurking silently inside his memory opens the possibility of his daughter’s questioning fate. A second layer of silence permeates through the “rescuers,” who are “eight young men equipped with a lorry and rifles” (Manto 1948, 75), pledging to help unite divided families. Sakina finds herself consoled and given a jacket to cover herself, and in the following paragraph, Sirajuddin receives no news of his missing daughter, only vague consolation. Only the doctor’s reaction indicates his grasp on the situation: perhaps he has figured out the intensity of the harassment. Ironically, what he feels is left at an open end: is he concerned with the young girl’s health, or does he intentionally choose silence while viewing another instance of casual harassment?

Manto’s characters as universal representations

Fallen into a homogenous mass, Sirajuddin symbolises the desperate everyman searching for their kin amidst the chaos. The most silenced in the story is the refugee crowd. Representations of the crowd are feeble and fuzzy, no one pays any heed to the other, and everyone needs equal help: everyone has a mother, daughter, or wife to rescue. However, the reader discovers that no female is named or identified (except Sakina). The mothers, daughters and wives are anonymous. They are everywhere, yet their presence in the story is outside the silenced crowd—the only named female, young teenager Sakina, has lost her voice. Sakina’s silence represents every form of cumulative torture women have suffered throughout partition. She represents women’s trauma not only during the traumatic exodus but is also “emblematic of the historical silences imposed on/around women…and their experience of sexual violence anytime, anywhere” (Chand 2006, 308). An almost lifeless Sakina performs an act of opening her trousers to an instruction. The reader can assume that she must have been forced to follow and later surrendered to that instruction until she was dumped off, deemed useless.

It is the accepted, silent “everydayness” of sexual violence that grips the readers. The mere possibility of what happens in the story representing the actual situation during the partition is enough to induce fear. For women, there is no division. Whereas partition borders divide communities into “them” and “us,” women are the unlucky lot facing the brunt of harassment from both sides.

Them “and” Us?

What makes this story spine-chilling is the unbothered conclusion depicting the normalisation of such sexual violence during partition. Usually, “ruining” the woman’s body, considered directly proportional to ruining her dignity, was deemed an easy revenge tool in communally violent nationalist movements. However, this action by the rescuers suggests that they might as well have been enjoying the liberty of violating numerous women behind the facade of “rescuing” them: the story mentions them rescuing “several women…and children” (Manto 1948, 75). It is the accepted, silent “everydayness” of sexual violence that grips the readers. The mere possibility of what happens in the story representing the actual situation during the partition is enough to induce fear. For women, there is no division. Whereas partition borders divide communities into “them” and “us,” women are the unlucky lot facing the brunt of harassment from both sides.

Conclusion

After 75 years, such acts of silenced and overlooked casual violence against females are still a burgeoning concern for the nation to address. Accurate and fact-checked data of casual violence against females have no place in the statist historical archives, let alone during refugee migration. Ironically, this collective silence about their tribulations strengthens the normalisation of sexual violence as expected, accepted, and silenced. As against women’s silences and state-imposed intentional ones, partition literature is an excellent source of alternate histories that alert readers to the grassroots situation of partition violence. Manto’s stories provide such alternate histories. In offering no direct moral, Manto’s story raises fingers at the “silence” audience and subconsciously makes them a part of the violators. Through such an attack, Manto’s story shows that even the sheer speechlessness of the protagonist, even today, can scream for help to break out of this everydayness of trauma. The audience is pulled into an uncomfortable, anguished recognition of their silence while reading the story’s crime against women unfold. Like his protagonist Sakina, Manto’s story represents a “human” history, instead of the data-driven, politically pointed statist history.

References

Butalia, U. 2000. The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India.

Durham: Duke University Press.

Manto, S. H. Open It. trans. M. Umar Memon. University of Warwick.

https://warwick.ac.uk/manto_kholdo.pdf

Sherry Chand, S. V. 2006. “Manto’s ‘Open It’: Engendering Partition Narratives.”

Economic and Political Weekly 41(4): 308–310.

Singh, A.I. 2006. The Partition of India. New Delhi: National Book Trust.

Arna Dirghangi is a Research Intern at CSPS