“The greatest emancipatory value for human freedom and the promise for liberty have not been the result of orderly institutional procedures, but disorderly spontaneous action cracking open the society.” – James C. Scott.

Yale Professor James C. Scott, who passed away on July 19th at 87, was one of the past century’s most original and radical political theorists. Born and raised in New Jersey, Scott received a Quaker education, profoundly influencing his worldview and politics. The values imparted by Quakerism focused on peace, equality, and community, shaped his work. At the same time, his early views on society and governance were influenced by participating in Quaker social gospel activities and volunteering at homeless shelters.

Scott studied political economy at Williams College, focusing on economics. However, a late-in-life romance distracted him from his studies, leading him to switch advisors to economist William Hollinger, who had a keen interest in the economic development of Burma (Myanmar). After completing his BA, Scott was admitted to Yale’s Graduate Program in economics. A conflict with a summer trip to North Africa led to his transfer to the Political Science department. Beginning as a political scientist focusing on Southeast Asia, Scott expanded his studies to other disciplines and regions. He wrote extensively about how authority exerts itself, how ordinary people resist or avoid that authority and the unmapped territories where resistance often occurs. His works explored figuratively and unmapped territories, such as Malaysian farmers covertly evading Islamic government tithes (zakat) by underreporting their rice yields and people escaping state power in uncharted marshes and mountains to escape state control and maintain their autonomy.

Scott’s work underlined the theme of resistance. He argued in his book, “Two Cheers for Anarchism” that the greatest value for human freedom and the promise of liberty often stem from disorderly spontaneous actions rather than orderly institutional procedures. In “Seeing like a State”, he propounded how governments attempt to track and map all activity beyond their knowledge and how authoritarians try to remould societies to make them more mappable. Besides writing, Scott’s bent on method led him to do long-term ethnographic fieldwork, which was unconventional for political scientists at the time. He spent fourteen months in a Malaysian village, research that formed the basis for his much-celebrated book “Weapons of the Weak.” This work garnered attention from anthropologists like Clifford Geertz and Benedict Anderson, marking Scott as a political scientist who effectively used ethnography in his methodology.

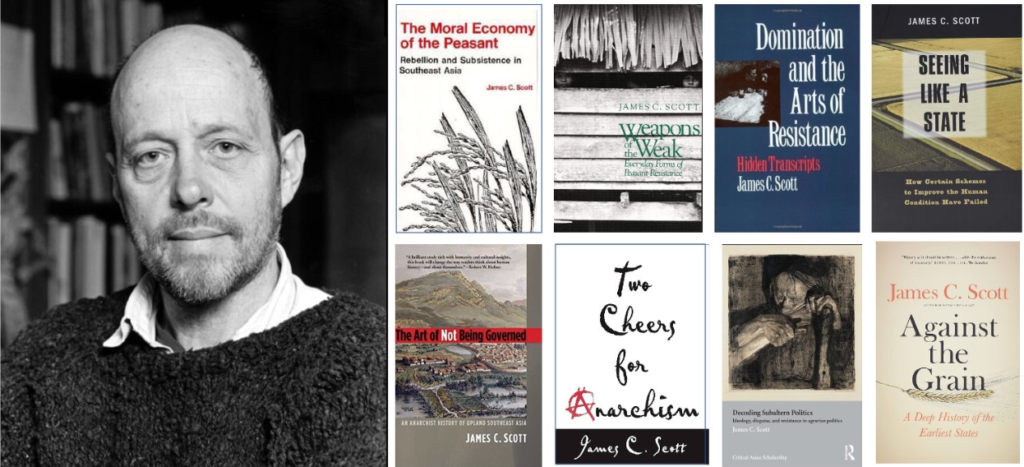

Scott authored ten books that spanned multiple disciplines and were unparalleled contributions to the interpretive social sciences. Scott may not have publicly identified as an anarchist, but his works often reflected on anarchist principles. In “Two Cheers for Anarchism,” he introduced concepts like “anarchist squint” and “anarchist callisthenics” to describe informal cooperation and routine violations of minor laws as a form of resistance. Scott’s philosophy emphasised that customs are a living, negotiated set of practices continually adapted to new ecological and social circumstances. He argued against romanticising customary systems of tenure, acknowledging their inequalities but also their adaptability.

Scott’s work profoundly influenced scholars, particularly those in the subaltern studies school, who recognized that most resistances do not speak their name. His book “Weapons of the Weak” provided a new lens to examine everyday acts of resistance, nudging sociologists and economists to consider actions like jaywalking and assembly-line slowdowns as forms of resistance against power structures. However, Scott’s works are not without criticism. He has been critiqued for ostensibly reducing the concept of revolution to mere resistance. Critics argue that Scott’s focus on everyday forms of resistance, as opposed to organised, large-scale revolutions, diminishes the significance of more structured, strategic efforts to enact systemic change. Edward Said, for instance, argued that analysing the hidden strategies of the subaltern undermined their ability to resist. This criticism raises broader questions about the nature of radical scholarship and whether dissecting resistance mechanisms tempers their potential.

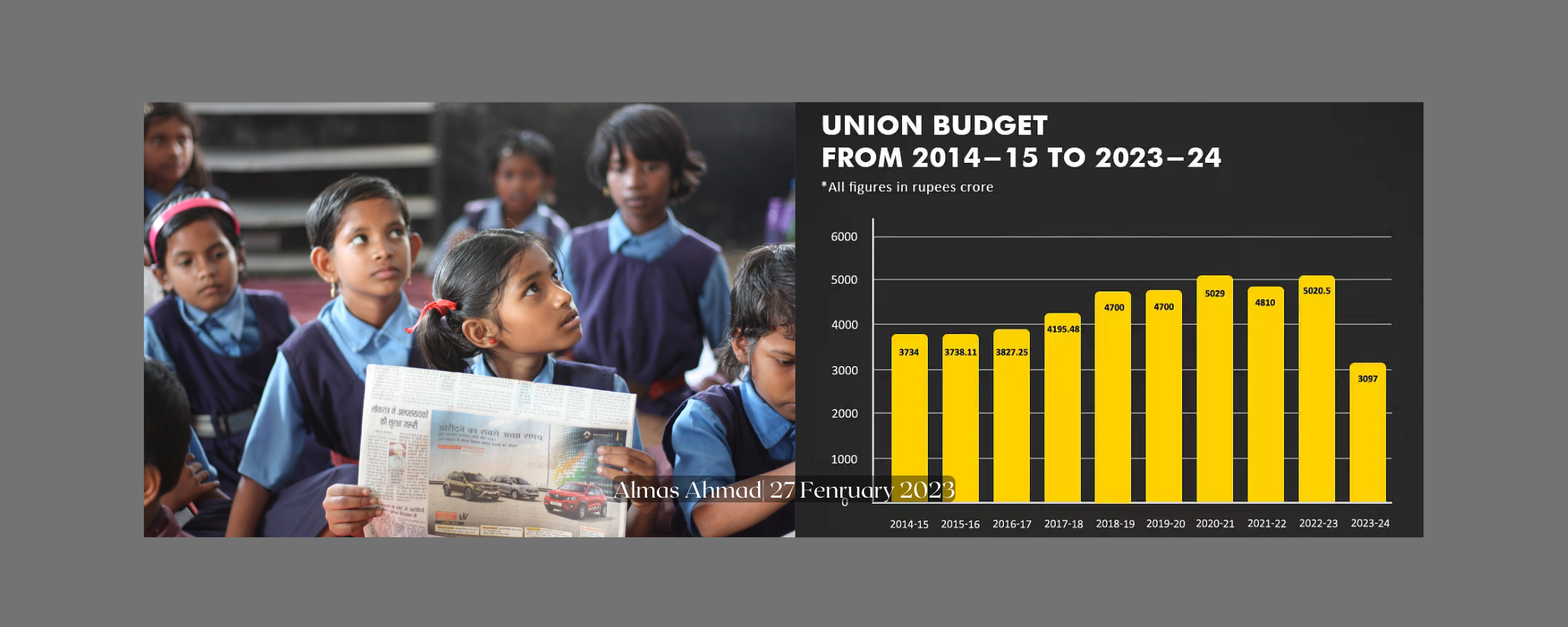

However, in the contemporary Indian political context, where avenues for protest are increasingly constrained, Scott’s notion of ‘everyday forms of resistance’ has salience. This concept refers to the subtle, often unnoticed actions of individuals or groups that challenge or resist power structures in their daily lives. The Scott’s framework offers a pragmatic approach for common people to persist and express resistance through non-confrontational means in times when the regimes have often been either against dissent or largely unresponsive to it which is evident from the increasing restrictions on public gatherings, limitations on free speech, and the use of both legal and extra-legal measures to suppress formal and informal opposition. This approach could be one of the means to survive in oppressive environments and, importantly, provides a lighthouse of hope for those seeking to challenge power structures. It offers a roadmap that is less likely to provoke severe repercussions and embeds a sense of hope in the face of despair.

James C. Scott will be remembered as a pioneering thinker whose ideas and scholarship continue to inspire and challenge scholars, activists, or anyone intrigued by social and political intricacies. His work, with its deep insights into the dynamics of power and resistance, will serve as an illuminant source, providing comfort and reassurance as we navigate the complexities of our world.

Deshdeep Dhankhar is associated with the Centre de Sciences Humaine (CSH) and Max Weber Forum for South Asian Studies (MWF). His research focuses on democracy, opposition and political behaviour.

Selected bibliography:

- Scott, J.C., 1976. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Scott, J.C., 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Scott, J.C., 1987. Resistance without Protest and without Organization: Peasant Opposition to the Islamic Zakat and the Christian Tithe. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 29(3), pp. 417–452.

- Scott, J.C., 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Holtzman, B. and Hughes, C., 2010. Points of Resistance and Departure: An interview with James C. Scott. Upping the Anti, Issue 11.

- Scott, J.C., 2012. Two Cheers for Anarchism: Six Easy Pieces on Autonomy, Dignity, and Meaningful Work and Play. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Teidi Productions, 2023. In A Field All His Own: The Life and Career of James C. Scott. The Oral History Center at UC Berkeley. YouTube.