In September 2022, the Consumer Prices Index – Combined (CPI-C), which tracks the changes in retail prices, recorded a 7.41 per cent increase. Similarly, food prices have increased by 8.6 per cent, resulting in hardships for common people. However, neither the aggregate numbers nor any systematic economic assessment can gauge the actual cost of the inflation that households face.

The literature broadly identifies three main sources of inflation-demand pull, cost-push and inflation expectations. At any given moment, there is a natural rate of inflation (core inflation) towards which actual inflation tends to incline and is determined by the difference between the growth rates of aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

For deploying appropriate policy for price stability, it becomes vital to understand the primary sources of inflation. The literature broadly identifies three main sources of inflation-demand pull, cost-push and inflation expectations. At any given moment, there is a natural rate of inflation (core inflation) towards which actual inflation tends to incline and is determined by the difference between the growth rates of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. On the demand side, apart from the growth rate of money, fiscal policy also impacts the growth rate of aggregate demand. Similarly, on the supply side, the growth rate in productivity in the long run and disruption in the supply of goods influence the price level in the short run. Therefore, it is not surprising that actual inflation will deviate from average inflation due to supply disruptions owing to climate change and the Ukraine-Russia war. As a result of which, both food and energy prices have increased.

Since the early 1990s, rule-based public policies have gained considerable popularity. In the area of monetary policy, Inflation Targeting (IT) emerged as a new framework which has often been praised and favoured for making price stability a primary objective of monetary policy. Following suit, India also adopted this framework in October 2016 after long preparations on the prerequisite of IT. Under this framework, the Union Government, in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), initially fixed the inflation target at per cent for five years. In March 2021, it was retained for the next five years. But, the question remains, does RBI control the current price surge? Though having a single instrument for a single objective is good, what if the instrument is not optimal? To put it in context, it will result in a situation where the medicine turns worse than a disease.

Inflation Targeting in India

The framework has been successful in India in many ways. For the year 2016-21, the level and variability have been low compared to 2012-16. Until Covid-19, inflation was well under control. The inflation expectation measured by surveys conducted by RBI of households and professional forecasters is declining in the IT period but higher than the upper limit, i.e. 6 per cent. As far as regional-level inflation is concerned, the number of states having inflation rates following the national level trend is 20 in the IT regime compared to 8 in the pre-IT period.

Though the RBI is primarily responsible for maintaining price stability under the IT framework, it does not mean that output is neglected. When inflation is in the comfort zone, the RBI has headroom to focus on other objectives, particularly output. The same was found during the pandemic when RBI reduced the policy rate by 115 basis points from March 2020-May 2020. The aim was to revive growth, ease liquidity conditions and channel it to specific sectors facing funding constraints.

The framework is also being criticised for choosing headline inflation as the nominal anchor over which RBI has no control. Even some committee members also emphasise targeting core inflation. However, targeting the same is rational as it reflects the cost of living more accurately. Further, changing the nominal anchor will result in credibility loss and create uncertainty and confusion. Nevertheless, the current CPI series is based on the consumption survey of 2011-12. It was updated in 2015 and still contains obsolete items like DVDs and audio cassettes.

In a globalised world, changes in the exchange rate also impact inflation, but the cross-country evidence show that it declines in the IT framework due to certainty in monetary policy.

In a globalised world, changes in the exchange rate also impact inflation, but the cross-country evidence show that it declines in the IT framework due to certainty in monetary policy. Nonetheless, the RBI also intervenes in the foreign exchange market to stabilise the rupee. The same has been highlighted by one of the committee members. This raises questions about the nature of the IT framework in India- whether it is de jure only or de facto.

The framework was also criticised for being hawkish, a result of which policy rates have been kept higher. But, as the data shows, the policy rates have been low compared to the pre-IT period. Even during Covid-19, the RBI was quick to decrease the same.

The transmission of monetary policy has been a concern in India. Former Governor Urjit Patel (2020) aptly summarised the incomplete transmission of monetary policy in the following words. “Between January 2015 and March 2016, the RBI reduced its benchmark repo rate by 125 basis points, public sector banks on an average reduced their base rate by 55 basis points, and private sector banks have cut their rates by 50 basis points”. The absence of effective transmission makes the achievement of the target difficult. Moreover, the RBI directed commercial banks to external benchmark lending rates to improve transmission. As a result, the share loans benchmarked to the external lending rate increased to 46.9 per cent from a minuscule percentage in 2019.

The monetary policy is designed based on forecasts for inflation and output gap. However, the RBI has been overestimating it most of the time.

The monetary policy is designed based on forecasts for inflation and output gap. However, the RBI has been overestimating it most of the time. Apart from this, sometimes contradictory decisions have been taken- lowering repo rate but conducting open market operations. There have also been issues on the communication front and decisions taken concerning monetary policy. These errors in estimations have serious policy implications. The RBI needs to work on these issues for better policy making.

Transparency and accountability

The monetary policymaking by the committee rather than the Governor, besides democratising decision-making, also insulated it from political pressure. However, Al-Jazeera in a series of reports, shows the prevalence of political pressure. In 2020, the inflation on average remained higher than the target for three successive quarters. But, the RBI did not submit any report for failing to meet the target. Instead, the political executive gave a free pass to the central bank by questioning its data. By doing so, the government validated the doubts raised on the Indian statistical system by critics for being dodgy, untimely and unrepresentative. The central bank got a free pass without worrying about accountability, and the central bank reciprocated by not hiking the policy rate. It was a win-win situation for both parties. The question is not how much the central bank influenced inflation and were the rate cuts necessary. It is about transparency, accountability and independence, which the central bank wields. The initial motive of adopting inflation targeting by New Zealand and other countries was to free monetary policy from the executive chains while ensuring democratic and transparent policymaking.

RBI has breached the target again for three consecutive quarters. Nevertheless, this time it has acknowledged the breach. Under the RBI act 1934, the central bank has to send a detailed report to the central government within one month of failure to meet the target. In the post-monetary policy press conference on 30th September 2022, the Governor maintained explicitly that we would not make the letter public.

Now the RBI has breached the target again for three consecutive quarters. Nevertheless, this time it has acknowledged the breach. Under the RBI act 1934, the central bank has to send a detailed report to the central government within one month of failure to meet the target. In the post-monetary policy press conference on 30th September 2022, the Governor maintained explicitly that we would not make the letter public. However, at the same time, he mentions “we are expecting the inflation to come down close to the target over a two-year cycle; that was our expectation earlier and even now. But then again, there are so many uncertainties that are playing out and coming in from time-to-time”. This statement contains a clue about the time frame which the RBI has in mind to bring inflation back into the target range.

The RBI is not sure whether they will be able to achieve the same. Add to this, the non-disclosure of the report raises questions about the RBI’s transparency and accountability. It will de-anchor the inflation expectations, which are crucial for the success of inflation targeting. Though, the act is silent about putting the report in the public domain. It would have been good for boosting the reputation of RBI for being transparent and committed to price stability. Nevertheless, the transparency and communication within and outside RBI improved with the publication of minutes of meetings and monetary policy reports. This results in the transparent evaluation and accountability of the individual members and monetary policy.

Good Policy or Good Luck

To put it in the words of Easterly et al. (1993), whether the early success of IT was the combination of both good policy and good luck? The impressive performance of IT contains some good luck as both agricultural production and fuel prices were muted. Chinnoy et al. (2016) have attributed the disinflation to a decline in the discretionary component of minimum support price and a decrease in global crude oil prices. With both fuel and food prices moving in the north direction, the framework is under criticism.

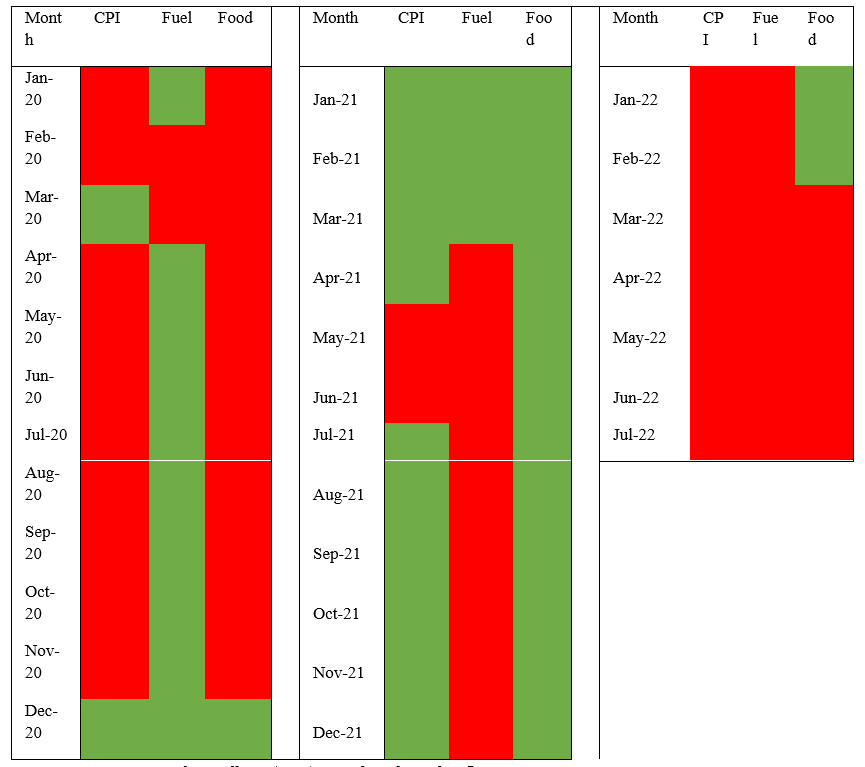

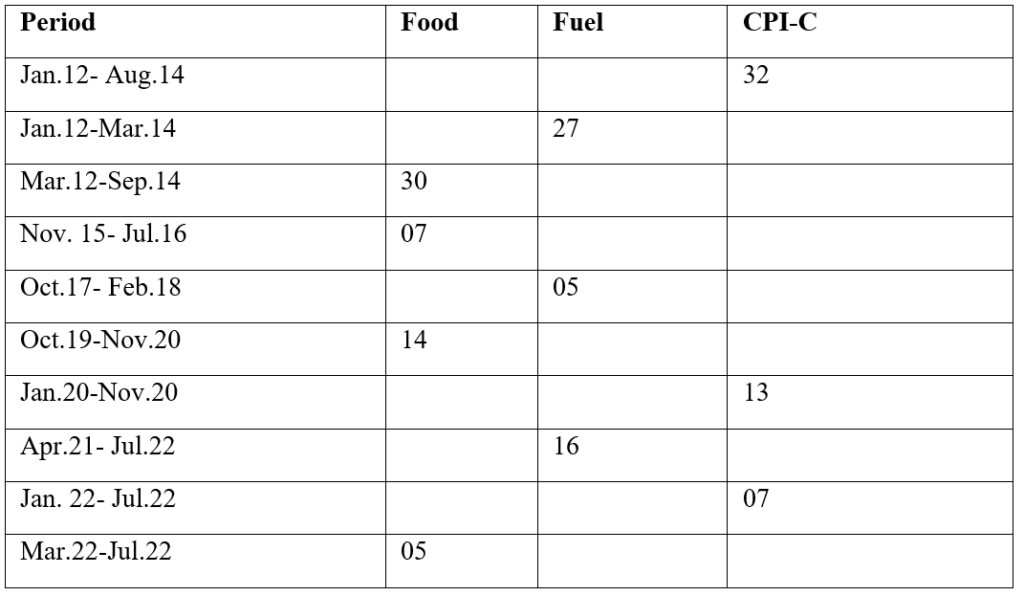

But, a close look reveals a different story, as current inflation persistence is much of the creation of government policies and pandemic concerning food and fuel (figure1). The RBI have no control over these matters. The success of an IT regime depends on other policies that make the task of monetary policy more straightforward and more credible. So, the blame on the framework is unfounded and untimely. Instead, the move should be towards more transparency and better accountability so that the same can be replicated to further other reforms in financial regulations.

Figure 1.Heatmap of Headline (CPI) Food and Fuel inflation rate since Jan. 2020. Note: The red and green represents inflation rate greater than and less than 6 per cent, respectively. Data source: Database on Indian Economy

Inflation in India: Made in India or Global

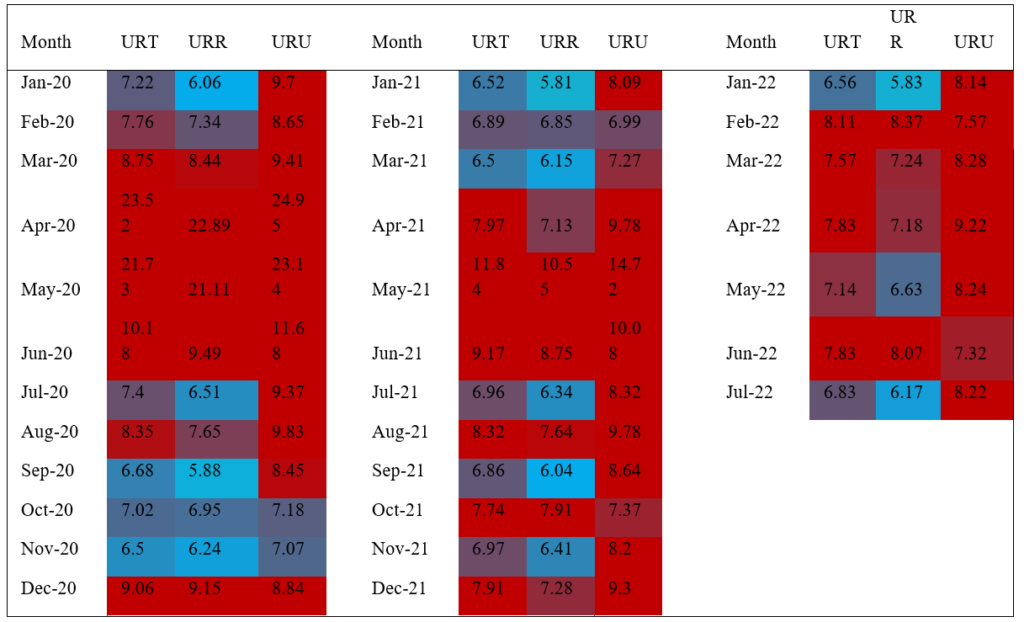

The main reasons for driving the current inflation have been mostly due to disruptions on the supply side. The supply shocks that reduce the overall supply ultimately result in cost-push inflation. Had the inflationary pressure been coming from the demand side, it would be logical to go for rate hikes. The fact is that the economy is still recovering from the pandemic with high unemployment (figure 2) . Furthermore, monetary policy impacts the economy with lags. The impact will be visible at a time when the growth will already be down. That time it will further slowdown the economy leading to further job losses. Therefore, policymakers must find the right balance between growth and inflation without sacrificing the other.

Figure 2.Heatmap of monthly unemployment rate of India.

Note: URT represents total unemployment rate, URR represents rural unemployment rate and URU represents urban unemployment rate.Source: centre for monitoring Indian Economy.

As already mentioned, the nominal anchor that the RBI target contains two components over which monetary policy has no control. These two components decide the direction of future inflation in India owing to their more than 50 percent weightage in the consumer price index. As the table 1 shows, from October 2015- November 2019, the inflation was only in July 2016 above the 6 percent target. The shows that between November 2015 and July 2016, food inflation was higher than 6 per cent for seven months out of 9 months. But, from April 2021 till July 2022, fuel inflation has been continuously greater than 6 per cent. The high excise duty on petroleum products is also partly to blame.

Table 1. Episodes of Inflation persistence (no. of Months)

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

A study by PRS legislative shows that the major component of Petrol and Diesel prices is the taxes levied by the Centre and states. Post Good and services tax (GST) implementation, the state governments have less autonomy in taxation policy, and since petroleum products are outside the GST regime, the states have the discretion to tax accordingly. In this context, Centre slashed excise duty on Petrol and Diesel in November 2021, followed by one more cut in May 2022. The finance minister even urged states to follow suit to ease inflation.

Conclusion

In the pre-Covid IT period, inflation was under control, and all hailed the framework for ensuring price stability. The low inflation phase resulted from both good policies and good luck. However, the increase in fuel prices due to higher taxes and the increase in food inflation during the pandemic has resulted in the breach of the target. The breach of the target in a time mired with uncertainty caused by the pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war and climate change-induced factors is expected. The optimal policy response for a breach is to be transparent and make the report public. That way, communication with the public, who are ultimate stakeholders, will improve.

A right step in this direction would be to expand its outreach by using the existing regional offices for public consultation concerning monetary policy. These consultations will aid the RBI in gaining a better understanding of the concerns of the common masses about the economy and economic policy.

Arshid Hussain Peer is a Research Scholar at Jamia Millia Islamia. Prof. Mirza Allim Baig is a professor at the Department of Economics at Jamia Millia Islamia.