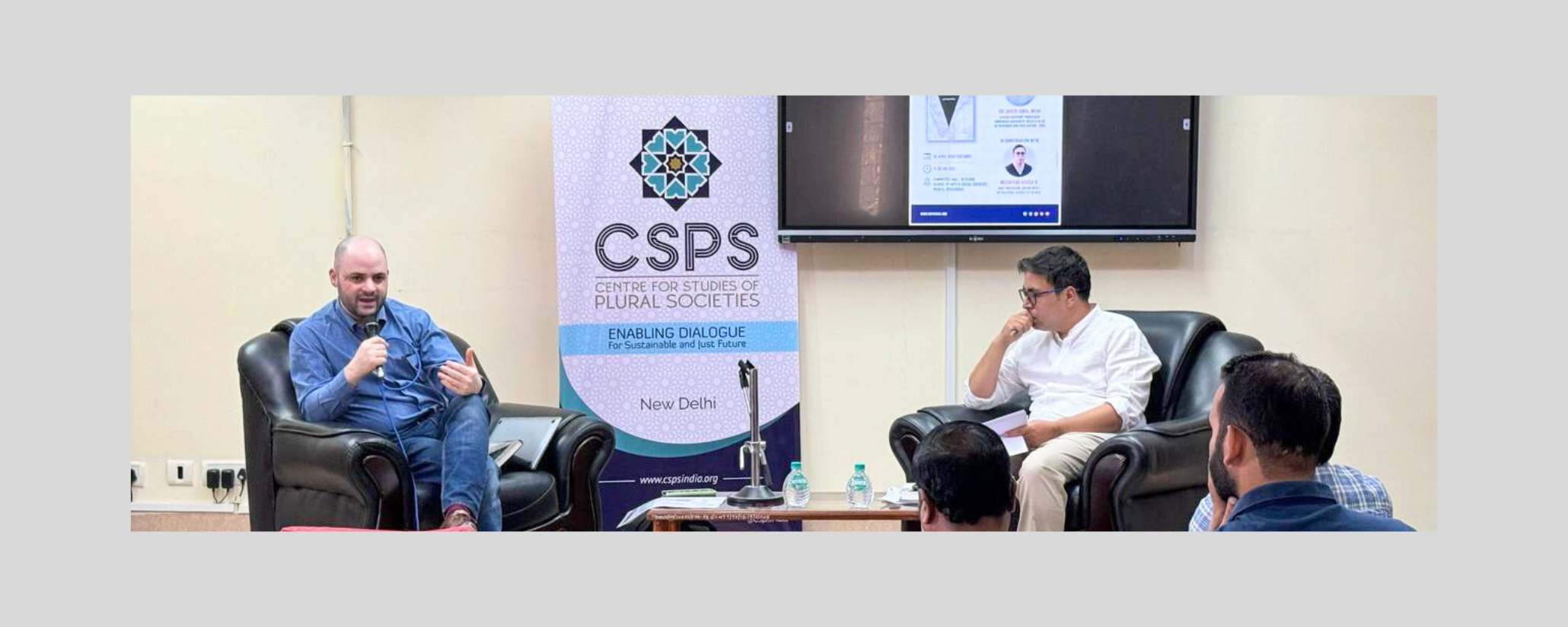

Centre for Studies of Plural Societies (CSPS) organised a book discussion on “Practices of the State: Muslims, Law and Violence in India,” authored by Professor Tanweer Fazal, a professor of sociology at the University of Hyderabad. Prof. Maitrayee Chaudhari, former professor of sociology at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi chaired the discussion.The session was moderated by Dr. Javed Iqbal Wani, Head of Research and Publications at the Centre for Studies of Plural Societies (CSPS).

Professor Tanweer Fazal commenced the session emphasising on the 5 essays that comprised his book as an exercise to decode the complexities of the Indian State and its evolution in interacting with society and Muslim communities in particular. He spoke on the projection of the scapegoating of minority communities as well as vulnerable citizenry amidst an emerging silence within academia that led legitimacy to the current regime. By interrogating the idea about whether a pre-2014 India lacked the same level of vitriol and aggression as the previous years, Prof. Fazal instead follows a historical and anthropological understanding of the state and calls for a reworking of analytical frameworks to decode the present state of affairs. He posited his work as a continuation of placing the state as a subject of analysis and weighs the Indian State’s substantive realities against its constitutional ideals.

Prof. Fazal makes a note to remind his audience that the question of ‘Muslims’ cannot and should not be treated as a monolithic community and instead as a collective of communities that interacts with larger institutions and collectives outside it. Simultaneously however, it becomes important to acknowledge that there is a level of vulnerability that a Hinduised state uniquely targets Muslim communities with. He starts by tracing the history of cow-slaughter laws and frames it through three different time periods; pre-independence, post-independence and post-2014, where he elucidates that while law and public order was given primacy in the previous two periods, there has been a shift in the past two decades towards open hostility and institutional impunity for perpetrators of violence. The author mentions the Shaheed Ganj Mosque, which came under Sikh occupation when later Muslim organisations petitioned for its restoration, but British courts, fearing public disorder, chose to maintain the status quo. Fazal notes the fundamental changes post-1947, with the establishment of deities within the Babri Masjid from 1950 onwards, the 1992 demolition to the Supreme Court verdict, reflecting shifts to address majoritarian anxieties. These instances showcased how earlier institutions and the state managed communal disruptions while also positing the post-2014 era as marking a shift towards triumphalism and defiance where the priority was no longer the preservation of law and order, but instead the accentuation and placating of majoritarian anxieties.

The discussion also touched upon the shifting ideological stance of the state from precolonial times wherein various theoretical approaches to understanding the state were examined, highlighting the importance of political economy and the relationship between the state and society. An anthropological analysis of the state, focusing on its experience by populations, was emphasised, particularly in situations of violence and crisis. The author in his discussion also examined the production of impunity in post-conflict incidents, such as the Bhagalpur riots of 1989 and the Ranvir Sena massacre of Dalits in 1997. He discussed how media narratives, court proceedings, and inquiry commissions contribute to impunity while critiquing the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and National Register of Citizens (NRC), which rendered 1.9 million people stateless in Assam.

Prof. Maitrayee Chaudhari, chairing the discussion, reflected on the rapid dismantling of past ideals. She took the example of the ‘Subcommittee on the Role of Women’ under the National Planning Committees of 1947 and identified three ideological strands: the socialist idea of a working class woman, the liberal idea of an individual unencumbered by caste or religion, and lastly, cultural nationalism, which has become more prominent as of late. Chaudhari emphasized the convergence of dominant societal forces with the state, subsuming academia, judiciary, and media into a nationalistic framework that seems to have gained currency in recent times. Prof. Chaudhari also spoke about how the past functioning of committees following a particular violent incident were set up as a means to resolve tension but ultimately failed to reach substantive resolutions. In the present context, there then comes a point where a belief that the state should follow ‘social law’ has taken root with the 2014 Lok Sabha elections being a populist, majoritarian articulation of grudges that previously may have gone unaddressed. These occasions of tensions get heightened in times of crisis, much like the COVID pandemic where there was massive inequalities, communal tensions and stark vulnerabilities in full display.

Prof. Fazal also highlighted instances where Muslims have been treated by the state, law and subjected to persecution because of a particular making of law, showcasing the way the state interacts with its constituents. He argues that one can understand community formations and the narrative of the ‘us versus them’ through a ‘Triadic lens’ where the state plays a central role in the construction of community boundaries. The triad consists of the nation-state at the centre, the communities on the spectrum and the national public on the other spectrum. The state and the national public have a close relation with the state drawing legitimacy from the national public who approves the bulldozing of houses and grants legitimacy to the state. This national public is then constituted and reconstituted according to political negotiations and the needs of those in power.

The discussion also saw questions raised about the ‘us versus them’ narrative being raised in states like Assam, to which the author posits that the process of ‘otherisation’ is one that is not new and instead follows a larger history. The superimposing of past boundaries, claims and the overlooking of histories such as when migration into the valley was sought by colonialists and land owners to overcome labour shortages, have instead given way to regional chauvinism that have translated into anti-migrant rhetoric and violence. The author also talked about how there is an evolving political articulation using the language of rights and citizenship that are now being wielded by the Muslim community alongside exclusionary aspirations of institutions and political forces.

The discussion concluded with reflections on the state’s relationship with society, the role of social media, and multivocality of the Indian State while pointing future researchers towards the need to map these evolving changes. Overall, “Practices of the State: Muslims, Law and Violence in India” offers a crucial lens to understand the intricate dynamics of state practices in India. Prof. Fazal’s work challenges us to critically evaluate the past and present, urging a deeper understanding of the state’s role in perpetuating violence and exclusion. The book discussion highlighted the need for continued discourse and analysis to address these complex issues and foster a more inclusive society.

The report is prepared by Callistine Lewis, a research intern at CSPS