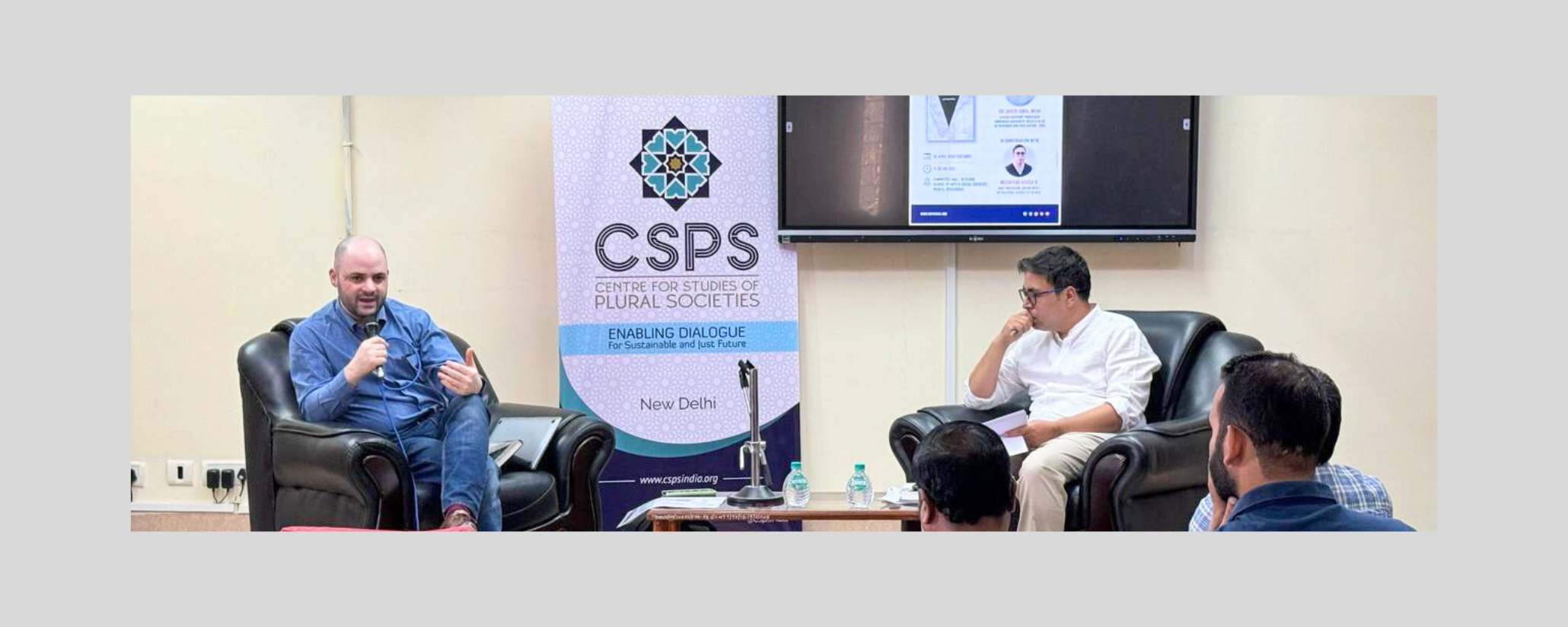

The Centre for Studies of Plural Studies (CSPS) hosted a book discussion on “Between Nation and ‘Community’: Muslim Universities and Indian Politics after Partition” by Dr. Laurence Gautier (Centre de Sciences Humaines). The session was chaired by Dr. Amir Ali (Jawaharlal Nehru University). It included discussants Dr. Irfanullah Farooqi (South Asian University), Dr. Javed Wani (Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University), and Dr. Mohd Osama (CSPS), along with doctoral candidates and students from various universities. The discussion’s focus was on the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) and Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI) as political sites that have shaped the location of Muslims in Indian nation-state after independence. Gautier highlighted that these educational institutions have historically played a significant role in shaping notions of ‘nation’ and ‘community’ in India and played a contested terrain between colonials and the colonised, shaping the Indian nation-state after independence. In the book, Gautier argued about the Congress’ ‘Muslim policy’ after independence, in which she explored the tensions between Congress’ secular nationalism and their attitude towards Muslim citizens. Over the years she has worked on questions of Muslim leadership and representation. She has also co-edited a special issue on ‘Historicizing Sayyid-ness: Social Status and Muslim Identity in South Asia’ (Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society).

The central theme of the book is around––how JMI and AMU emerged “as crucibles for competing conceptions of ‘Indian Muslimness’ in post-independence India.” The objective of the book is to locate Muslim politics post-independence and demonstrate how these institutions became a site for building the idea of community as a ‘composite nation’ in opposition to the majoritarian narratives. Moreover, how partition shaped their political stances, paved the role of the university in nation-building, and national integration. To do this, she uses rigorous methodological tools such as data from the archives, autobiographical accounts, newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, combined with the in-depth interviews.

She further explained how the university has developed various pedagogical methods and social experiments to provide modern education to Muslim students, primarily from ther elite backgrounds, to envision Muslim leadership for the ‘Muslim Quam.’ Also, building a foundation for a new education system inspired by the Gandhian model for post-independent India by connecting concepts to the practical world. Moreover, introducing the languages of Urdu and Hindi as medium of instruction to give space to the non-elite population. These institutions also aimed to overcome the trauma of partition and address the issue of the marginalisation of Muslims. The scholarship addresses ambiguities in the popular image of Congress as a secular nationalist, arguing about the presence Congress’ anti -Muslim bias and the imposition of majoritarian Indian culture. At one point, the state did not encourage a separate electorate but, at the same time, approached Muslims as a separate population through these institutions. The author cites instances where Jamia received less attention than AMU. At one point, the state did not encourage a separate electorate but, at the same time, approached Muslims as a separate population through these institutions. The author cites instances where Jamia received less attention than AMU–J. L. Nehru was anxious and considered the AMU to have the potential to trigger an arsenal, central to Muslim politics and separatism. For JMI, Zakir Husain challenged the contrary popular belief that Islam spreads communal politics by emphasising the values of service to the nation, which is a patriotic stance inspired by Islamic principles.

Elaborating on the resurgence of minority politics with questions on the demand for minority status as Muslim politics within institutions. She addressed the issues of Muslim quotas, issue-based coalitions of inter-religious groups, and vote bank politics in the book. Moreover, it highlights the absence of political actors or dominant Muslim parties in North India. With the Babri Masjid demolition, there was an emphasis on finding alternative strategies for minority politics. Therefore, the issues of development and economic and social justice gained more momentum than Muslim identity politics. Simultaneously, part of student bodies founded under Islamist groups emphasised Muslim superiority by defending Islamic values as ‘empowerment’ that minority politics failed to capture. In the process, there was a rise of communal politics on the campuses of AMU and the assertion of Jamia as a symbol of Muslims as opposed to Gandhian institution: J. L. Nehru was anxious and considered the AMU to have the potential to trigger an arsenal, central to Muslim politics and separatism. For JMI, Zakir Husain challenged the contrary popular belief that Islam spreads communal politics by emphasising the values of service to the nation, which is a patriotic stance inspired by Islamic principles.

The author explained the women’s education trajectory by tracing it from the margins to the central position. These institutions were primarily created by men for men, and women’s education was taken as a nationalist and a class project. With Islamist politics, women were pressured to assert their Muslim identity and be vanguards of the institution. They were critiqued and tagged as ‘betrayals’ for critiquing Muslim personal law and institutions. Gradually, they developed negotiations to locate themselves in the institution by asserting their access to the right to education rather than from an approach of gender rights and disparities. As per the Sachar Committee report, women were either pressured to take part or to safeguard their community. On the contrary, with recent mobilisation, women played leading roles in the protests in 2012, 2015, and the Pinjra Tod Movement protests to access the AMU central library. Women have emerged as political agents where religion informs their decisions. We witness progress wherein women are not questioned for taking a political position during the protests against the Citizenship Act. The author also highlights the presence of multiple identities in the Muslim community. She counters the homogenised image of Muslim women with formation and reformation beyond monolithic categories by situating women in relation to different marginalised socio-economic backgrounds.

The session was concluded on a note highlighting the importance of understanding institutions and their central role in locating Indian Muslims’ position in the Indian nation. The floor was open for comments and questions from the participants. The author further engaged in the discussions around the scope of further research in the context of JMI playing a role in anti-CAA protests in 2019 and the leading role of women at the forefront of the movement. The women reclaimed their political agency and their stand with mobilisation on campus. There was significant discussion around Urdu which is arguably a language of elites and a cultural symbol, related more to class than communal politics, to which the author cited a nuance study–on how Urdu aided in gaining access to education and employment for marginalised Muslims in Bihar. Finally, the author responded to comments on the current depoliticization of the JMI after the anti-CAA protests as compared to the Universities in the global West which are protesting on important political issues. The international political movements have shaped the political consciousness and the responses of students at the institution throughout history. However, in the present, the strategy of silence used to depoliticize the campus can be understood by understanding the parallels from student movements in global political history.

The report is presepared by Taskeen Nazir, a research intern at CSPS